Cold War Warrior and Test Pilot

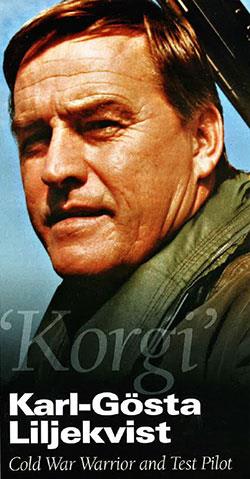

There is a remarkable Swedish pilot who now calls Australia home. Living in quiet retirement in a small town outside Melbourne is Karl-Gösta Liljekvist, or ‘Korgi’ as he is known to his friends and family, and his is a truly fascinating story.

by Nigel Pittaway for AERO Australia magazine (reproduced with permission)

He has also ejected at low level from a stricken aircraft and abandoned another on the ground after the engine exploded. The writer was recently privileged to meet Korgi and record some of his remarkable adventures for AERO Australia.

A PASSION FOR AVIATION

Korgi was born on 24 July 1936 at Tjärholm ìn the county of Ostergotlands Län and grew up in Finnkroken, near Valdermarsvik south of Stockholm, on Sweden's Baltic coast. Although neutral during the Second World War, Sweden was nevertheless affected by events and Korgi remembers smelling the smoke from fires burning in Gdansk and Warsaw which had drifted across the Baltic, following the Nazi invasion of Poland.

The aviation bug bit just after the end of the war when, in 1946, a young Korgi spotted an article in a local newspaper reporting the impending visit of a seaplane which would require drums of aviation gasoline to be positioned on a nearby island.

Korgi's father was the local fuel agent for Esso at the time and so, on the day the aircraft arrived, the ten-year-old took the ferry across to the island and walked seven kilometres to tell the pilot about the fuel, in the hope of being rewarded with a flight back to Finnkroken. The pilot, Per Loven, was a friend of his father and only too happy to oblige, so Korgi climbed into the Republic Seabee and from that moment on knew he wanted to be a pilot.

At the age of eighteen and having just graduated from high school, Korgi announced that he wanted to join the air force and be a fighter pilot but, because he was not yet 21, he needed parental approval to do so. Unfortunately his father would not sign the paperwork because he feared his only son would be killed.

"l said that if he didn't sign it I would sign it myself as soon as I was 21," he remembers with a smile. “After a year or two of pestering he gave up and I joined the air force when I was 20."

COLD WAR WARRIOR

Korgi joined the Swedish Flygvapen (Air Force) in October 1956 and reported to the Krigflygskolen (Central Flying School) at Lungbyhed in southern Sweden to begin his training.

The day following his arrival at Lungbyhed the young Korgi flew his first training flight with an instructor aboard a Saab Sk 50 (Safir) and soloed after 15 hours of dual training. Korgi and his classmates also flew the de Havilland Sk 28C (Vampire I55) during their time with the flight training school.

Twenty-four other candidates began their training at the same time and Korgi would graduate seventh out of the fifteen who would finish the course. He had flair for instrument flying, an attribute which would shape the remainder of his career. "l wanted to fly fighters, in fact the J 29 Tunnan ('Flying Barrel') at Linköping, which was near my home, but I was rather good at instrument flying, so they sent me to night fighters," he says with a grin.

During his air force career he was known as 'Kalle', a common Swedish diminutive for Karl. The 'Korgi' monicker was bestowed upon him in his later career with Saab, as the initials K-G are pronounced 'kaw geer' in Swedish.

Swedish Air Force policy is to leave pilots at a certain base for most, if not all of their operational careers and in 1957 Korgi was posted to Flygflottilj 1 (No. 1 Wing) at Västerås, west of Stockholm, to fly the de Havilland J 33 (Venom) night fighter.

Two years later the Venom was replaced by the Saab J 328 Lansen, a fighter version of the earlier A 324 'attack' Lansen and known to its crews as the 'Lansen Sport' because of its enhanced performance.

"The Venom was a good night fighter in its day and we had an infra-red sight, developed in Sweden, that was quite revolutionary really," Korgi remembers. "But the Lansen was better; it had an afterburner!"

Korgi's first brush with death came on 3 October 1960 when he and his navigator were forced to eject from a Lansen shortly after take-off from Västerås, following an engine failure.

"We had a problem with the RM6A engines [Rolls Royce Avon, licence built by Volvo Flygmotor and married to a Swedish, designed afterburner] as they were stored in a mountain tunnel in Sweden, conserved before being placed there and de conserved afterwards. We had heaps of engine failures at that time and I had worked out that the filter was clogged up," he says modestly.

"Basically the engine didn't stop but went to ground idle RPM and it was impossible to accelerate it. The only way to clear it was to shut it down and perform an in-flight restart but when it happened to me we were at such a low level [500m/1640ft] that my navigator and I had to eject."

Swedish radio announced almost immediately that a Lansen, flown by Service Airman Karl-Gösta Liljekvist had crashed, but didn't provide any further details. When Korgi telephoned his mother an hour or so after the crash to tell her that he was unhurt he found her in tears, thinking he was dead.

The cold war was in full swing by the mid-1960s and a highlight of night fighter operations was the interception of American spy flights over the Baltic. These flights were known as the 'tram' by Swedish pilots, due to their very predictable course over Denmark and up the middle of the Baltic Sea. The intercepts flown by the Swedes were not so much aimed at deterring the Americans, but observing the reaction of Russian air defences in Poland and the Baltic states.

DOUBLE DELTA

ln 1968 the Lansen began to be replaced by the supersonic Saab J 35D Draken and Korgi was posted to the Försökcentralen (Swedish Air Force Flight Test Centre) at Malmslätt near Linköping, initially in the planning division but flying both the Lansen and Draken as well.

After a while, Korgi became responsible for acceptance testing of Drakens coming off the Saab assembly line in Linköping and during this time he decided to see how far a Draken could fly without refueling on a trip home from the north of Sweden. To cut a long story short, Korgi landed back at Malmslätt with not enough fuel to taxi to the parking bay, which earned him a dressing down.

"We were young and carefree and sometimes did crazy things," he says with a wry grin. Whilst with the test centre, Korgi was involved in an event that would further shape his later career. The 'double-delta' configuration of the Draken was prone to a phenomenon known as the 'super-stall' where the elevons are blanked at high angles of attack and become ineffective. This resulted in several crashes early in the Draken's operational career and the loss of a number of pilots.

"One day, Karl-Erik Henriksson, a senior test pilot, came to me and said, 'Kalle, we have to find a way to recover from this superstall'," Korgi recalls. The two pilots took a two-seat Sk 35C Draken to an altitude of 15,000 metres (49,200ft) over Lake Vattern, one of the two great lakes in southern Sweden, to minimise damage should the attempt fail.

"We didn't think we would come back and we were prepared to eject. We kept the engine at full power and experimented with pulling and pushing the stick on the way down and we found a way in fact, by pushing the stick hard forward once the oscillations had stabilised," he remembers. "It was quite interesting really."

Korgi and Henriksson recovered the aircraft at a mere 500 metres (1640ft) and returned to Malmslätt to write the procedure which would be used right up until the end of Draken flying and save countless lives in the process. As a result of this work, Korgi was made a member of the Society of Experimental Test Pilots (SETP).

By the end of the 1960s Korgi, then a Sergeant, had obtained an engineering degree and was offered a position at Cadet School to become an officer. However the head of testing at Saab, the famous lgmar Rasmussen, offered him a testing position with the company. "lt was easy really, Saab offered at least double what even the most senior air force officer was paid," he says.

SAAB TEST PILOT

Korgi joined Saab on 1 May 1971, initially involved in the production test flights of Draken and Sk 60 (Saab 105) aircraft and later the mighty JA 37 Viggen.

One of his early tasks was to carry out runway arrested landings with a hook specified for a version of the Draken being developed for the Royal Danish Air Force and later he was involved with ferrying aircraft to Denmark on their delivery flights. "Heaps of Tuborg beer came back the other way," he remembers with a smile.

Korgi also delivered the first Draken to the Finnish Air Force in 1972, arriving in Helsinki to a blaze of television lights and a barrage of questions from the local media.

On 9 October 1973, he was accelerating down the Linköping runway in an AJ 37 'attack' Viggen when, at 70 knots, a fan blade from the first stage of the RM8A (JT8D-22) engine failed and entered the fuel tank just behind the cockpit, causing a major fire.

"All ejection parameters were met but because I was still on the ground I didn't want to eject; when you have your feet on the ground you don't think about bailing out, so I steered the aircraft off the runway into the mud and it stopped pretty fast," he recalls.

"The aircraft was on fire, I was on fire, and I jumped from the cockpit to the ground, but the Viggen is a large aircraft and I landed on my heels and the shock injured my pelvis." It was a singed and limping Korgi who walked back into the hangar after being picked up on the airfield, to inform the ground crew that the aircraft was broken and asking could he have another one please?

Another memorable moment came at the Farnborough Air Show in 1974 when Korgi flew a scintillating Viggen handling display in weather so bad that no other aircraft would fly. The display was flown in front of Sweden's King Carl-Gustav, with one wingtip actually in the 600 feet overcast during the tight turns. Although his masters at Saab were pleased by the display the British were not and Korgi earned the ire of the SBAC Flying Safety Committee!

During this time several Saab test pilots, including Korgi, were seconded back to the air force on numerous occasions to fly night ELINT and low-level photo-reconnaissance missions against the Soviet Union Using various models of Viggen, the flights were very dangerous, conducted at very low level and at supersonic speed, often at night. "Oh, I was very close," he says with a twinkle in his eye, when asked how far away he was from Russian territory.

One of Korgi's other tasks was to fly a series of ejection seat trials, using a modified Lansen with a live seat in the rear cockpit. It was during one such test firing that he almost came to grief. The ejection of the rear seat caused his seat to partially activate and, although it didn’t actually fire, the sequence released his harness and operated the seat separation mechanism. Korgi found himself with his face forced against the windscreen with the stick back between his knees, but managed to recover the aircraft and land safely.

By now Korgi was an experimental test pilot and, in addition to his production test flying, he became involved in a number of trials with the Swedish Air Force including flying a Viggen in excess of Mach 1 and at an altitude of between 50 and 100 metres (!) over the Vidsel range in north Sweden, to see if the pressure wave could be used to destroy enemy radar sites. "It was good fun," he says.

THE CIVIL SIDE

With the development of the Saab 340 (and later 2000) regional turboprops, Korgi entered the final phase of his flying career. Conducting both experimental testing during early development and later production testing, he finally achieved the position of Chief Production Test Pilot - Civil Aircraft.

Korgi demonstrated the 340 and 2000 all around the world: in North and South America, Europe, the Middle East, Asia and Australia. He also spent considerable time in different parts of the world flying commuter services alongside local pilots as they built up their skills.

As fate would have it, one of the demonstration tours Korgi commanded was to Australia in 1990 with a 340B (c/n 207) destined for Hazelton Airlines as VH-OLN. The aircraft was met in Darwin by a lady called Judy, the marketing co-ordinator for Saab in Australia. The three-weeks tour basically circumnavigated the country in an anti-clockwise direction demonstrating to local airlines and media representatives along the way.

Fast forward to 1997 and Korgi, now married to Judy and living in Linköping, is preparing for retirement in Australia. "It was a democratic decision, we had both been married before and she had a bigger family than me," he remembers.

Korgi's last flight for Saab was the delivery of a 340B to the USA as he and Judy made their way to Australia and retirement in November 1997. He finished his career with around 4000 hours in his log book - a modest total for a 40-years flying career perhaps, but one which reflects many satisfying years in the relatively low tempo experimental world.

Due to her neutral stance and geographical position (situated between NATO and the Warsaw Pact) during the Cold War, Sweden had to develop an independent and innovative aerospace industry and Flygvapen pilots had to learn skills and tactics to overcome the Soviet Bloc's numerical superiority.

Korgi is very much a product of these Cold War needs and, together with many of his comrades, has even more stories to tell of derring-do against the odds.

Looking back on 40 years of exciting flying and adventure, Korgi doesn't hesitate when asked what his favourite aeroplane is.

"The Draken," he says. "The Viggen was as good as an F/A-18 Hornet, but I spent a lot of time in the Draken cockpit and it was very advanced for its day. We had a datalink in the 1960s, decades before the west, and it was fun to fly."